In the shadowed valleys of Utah’s rugged landscape, a forgotten chapter of American history lies buried beneath layers of silence and myth. The Mountain Meadows Massacre of 1857 represents a dark tableau of religious fervor, frontier violence, and human vulnerability—a moment when faith transformed into a brutal instrument of destruction. Paul Hutton’s landmark work ”American Primeval” peels back these layers, revealing a harrowing narrative that challenges our comfortable understanding of westward expansion and religious settlement in 19th-century America. Through meticulous research and unflinching prose, the book confronts a tragedy that has long been whispered about but rarely examined with such forensic clarity—a massacre that would forever mark the Mormon frontier with blood and shame. In the desolate wilderness of Utah Territory, a dark chapter of American history unfolded that would forever stain the landscape with blood and betrayal. The Mountain Meadows Massacre represented a shocking collision of religious fanaticism, frontier survival, and brutal violence that would challenge the very foundations of frontier morality.

On September 11, 1857, a wagon train of emigrants from Arkansas, traveling through southern Utah, became the target of a meticulously planned and executed attack. Local Mormon militiamen, alongside Native American allies, orchestrated a calculated assault that would result in one of the most horrific mass killings in 19th-century American history.

The wagon train, comprised of approximately 140 men, women, and children, found themselves trapped in a deadly scenario that would expose the complex tensions brewing in the Mormon-controlled Utah Territory. Led by local Mormon leaders, including John D. Lee, the attackers initially disguised themselves as Native Americans, launching a siege that would last several days.

After a prolonged standoff, the militiamen negotiated a treacherous surrender. Under the guise of safe passage, they separated the adult emigrants from the children and systematically executed nearly every adult. The youngest survivors, deemed too young to remember the massacre, were subsequently adopted into local Mormon families.

The brutality of the event revealed deep-seated tensions between Mormon settlers and non-Mormon emigrants. Brigham Young, the influential Mormon leader, had cultivated an environment of extreme suspicion toward outsiders, viewing them as potential threats to the religious community’s survival.

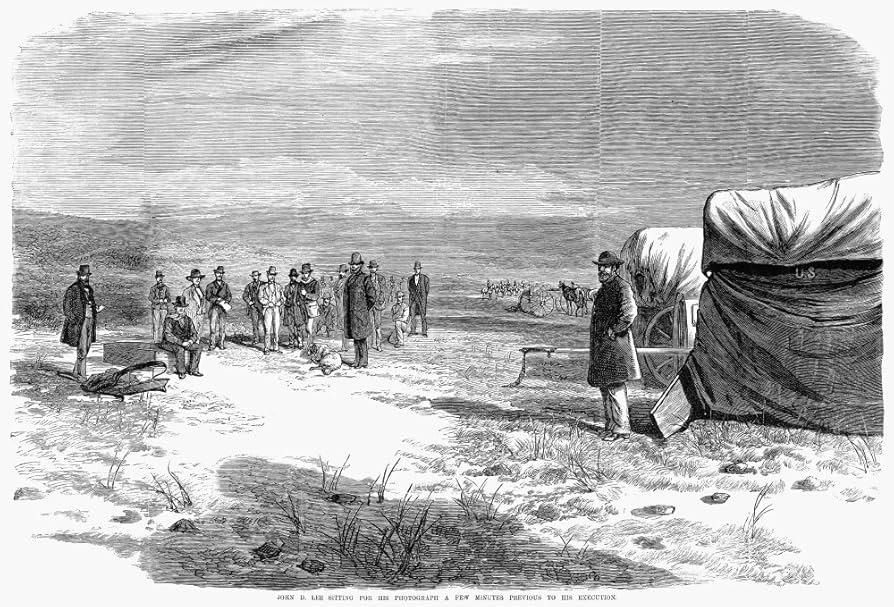

Investigations into the massacre were slow and politically complicated. John D. Lee would ultimately become the sole legal scapegoat, tried and executed nearly two decades after the event. However, the broader systemic failures that enabled such violence remained largely unaddressed.

Modern historians continue to dissect the complex motivations behind the massacre. Religious paranoia, territorial tensions, and a siege mentality contributed to creating an environment where such extreme violence could occur. The event stands as a stark reminder of how ideological extremism can transform seemingly ordinary individuals into perpetrators of extraordinary brutality.

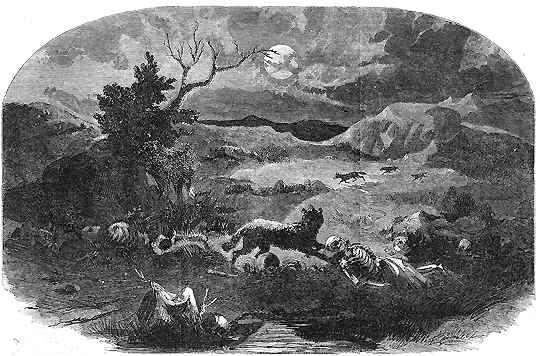

Archaeological evidence and survivor accounts have gradually unveiled the full horror of that September day. The landscape of Mountain Meadows remains a somber testament to a moment when religious conviction transformed into unimaginable violence, forever altering the narrative of westward expansion and religious settlement in the American frontier.